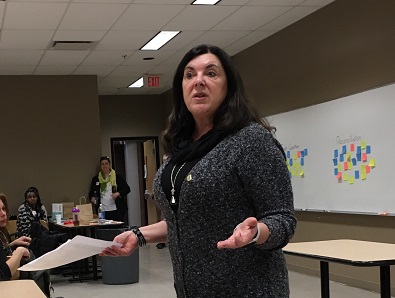

University of Regina President Vianne Timmons. Photo courtesy of Manfred Joehnck.

University of Regina President Vianne Timmons shared a deeply personal story about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder today when she addressed a national symposium on the disability being hosted at the U of R.

It was the story of a little girl named Kelly, who was just six when Timmons adopted her. It was not until later that she learned the child was afflicted with a life-long disability, which was caused by her mother’s drinking.

FASD is 100 per cent preventable, but back in the early 1970’s, not much was known about the connection between a woman drinking while she was pregnant and the impact it was having on her baby’s brain development.

It causes learning disabilities, lack of emotional control and lack of social development. In severe cases, the child’s face is abnormal and even some organs may not be formed properly.

Timmons says she learned about the disability as she raised her daughter, who is now 36, and wants her story shared.

“When I look at my daughter, she could be in prison easily because she doesn’t understand consequences, she takes everything literally,” she said. “Yet she is bright, and articulate, and intelligent, and so you know, you have all these conflicting attributes for your child.”

Symposium Facilitator and FASD researcher Michelle Stewart says the national gathering is a response to recommendations for the call to action in the Truth and Reconciliation Report.

“An event like this produces a space where we can kind of take some time to think of reconciliation together from various perspectives,” she said. “The event is more about taking up the spirit of reconciliation and the calls to action more broadly.”

Two of the recommendations in the Truth and Reconciliation Report dealt specifically with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, dealing with prevention and intervention, with a focus on culturally appropriate programs for Indigenous peoples.

It is estimated that between one and five per cent of children are born with FASD.

A 20-year study done in Saskatchewan from 1973 until 1993 examined 207 cases of FASD. A total of 178 — or 86 per cent of them — were Aboriginal, which is about seven times higher than the non-Aboriginal rate of 29.

Most experts agree, the disability has not been accurately tracked, so it is difficult to get a precise statistical look at rates either in the Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal community.

Most estimates are a best guess, ranging from one to five per cent.