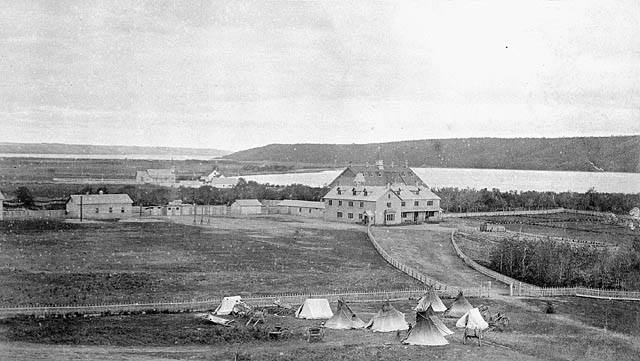

(Photo of Lebret Residential School)

WARNING: Disturbing content

By: Shari Narine, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Windspeaker.com

Senate Standing Committee on Indigenous Peoples chair Senator Brian Francis calls a report released July 19 a “road map” to help survivors of Indian residential schools and their families.

Honouring the Children Who Never Came Home: Truth, Education and Reconciliation is a 30-page report that examines the progress made—or lack of progress, as Francis says— on turning over Indian residential school records, which are important to identifying children’s remains buried in unmarked graves.

On March 21, the Senate committee heard from representatives from the Office of the Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools, and the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Francis says he was “absolutely” surprised to learn that residential school records were still outstanding.

Witness Donald Worme, independent legal counsel with the office of the special interlocutor, told the senate committee, “The most important relationship is with the federal government, yet it did not compel them to release records. Their signature on the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, under which they agreed to provide all relevant records to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission relative to Indian residential schools, was not complied with, and neither did the church entities comply.”

Not only is the federal government and a number of Roman Catholic entities dragging their feet in producing records, but so are Library and Archives Canada and the governments of Manitoba, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories.

The Senate committee has compelled all those parties to appear before them in the fall.

“The committee expects that witnesses will accept the invitation to appear so that they can explain why they have not yet released their records (that) families and survivors have already waited for for too long,” said Francis.

The committee has the option to summon witnesses who don’t accept the invitation, but Francis says he’s hoping they don’t have to take that action. But he will summon them if it’s necessary, he promises.

Compelling their presence is one of six recommendations put forward by the committee, which is also seeking a December update from Library and Archives Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations as to the transfer of records.

The committee is also recommending that the federal government take whatever steps necessary to combat the rise of residential school denialism in Canada.

“Being a First Nation person myself and a former chief of my community, it’s disappointing, but not surprising,” he said.

Francis served as chief of Abegweit First Nation for three terms. When he was appointed to the Senate in 2018, he became the first Mi’kmaw/Lnu to represent Epekwitk/Prince Edward Island. He also serves as the caucus chair of the Progressive Senate Group and is a member of the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans.

Communities are experiencing the “violence of denialism,” Special Interlocutor Kimberly Murray, a member of the Kahnesatake Mohawk Nation, told the Senate committee on March 21.

“Every time an announcement of anomalies, reflections or recoveries are made, communities are being inundated by people emailing or phoning them to attack them and saying, ‘This didn’t happen,’” she said.

Senator Mary Coyle categorized denialism as “really dangerous.”

It’s a sentiment with which Francis agrees.

“Denialism involves not only the complete denial of the existence of residential schools that have lasting impact, it also involves attempts to excuse, minimize, or deny basic established facts and survivors’ accounts,” he said.

“Denialism needs to be confronted and challenged wherever possible.”

Stephanie Scott from the Roseau River Anishinaabe First Nation, the executive director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, suggested legislation “to deal with” websites that support denialism.

While the committee didn’t specifically mention legislation in its direction to Canada to address denialism, Francis said that is a step he supports.

Murray also suggested legislation to make First Nations policing an essential service.

“We need some movement around First Nations policing, because I see an important role for them in the future investigation of missing children,” she said.

Murray believes that other policing services, including the RCMP, could not carry out investigations because they were involved in apprehending children and taking them to residential schools.

Murray also suggested legislation that would allow access to private lands that contain suspected burial sites.

“We need access to land. This is what keeps me awake many nights, thinking about how some things could escalate. We have landowners that aren’t allowing survivors onto properties, even to do ceremony, let alone to search the grounds,” she said. “My office has had to write letters and have meetings with landowners to try to convince them that this is the right thing to do. We have landowners that have campers on top of the burials of children — known burials. We don’t have any law to put a stop to this.”

The committee’s report does not recommend legislation in any area, but Francis says that was not a deliberate decision.

“We’re not shying away from anything here. Let’s be clear. I’m an Indigenous person myself. I’m the former First Nation leader. We’ll look at everything we can to do this and do it right for our people, for our children who never returned home,” he said.

The report does not use the word “genocide” when talking about Indian residential schools although the word is used numerous times during testimony.

“It was probably just an oversight,” said Francis. “I use the word ‘genocide’ myself all the time in speeches that I make. It is genocide and we have to call it what it is.”

Francis says the six “practical” recommendations in the report, which also include extending the Residential Schools Missing Children–Community Support Fund until 2033 and “adequate, predictable, stable and long-term funding” to the national centre so it can fulfil its mandate, are only a starting point.

“You see the effects in the community of the residential schools and the harm, the intergenerational trauma and it’s still alive and well today and yet the government dragged its heels on moving forward to help us as always. (It’s) like we have to be the ones that try and move this forward when it shouldn’t be that way. The harm was done to us. We didn’t do the harm to anyone else,” said Francis.

The steering committee will decide this fall the number of witnesses and the number of meetings to be scheduled, says Francis, in order to find out from entities and organizations as to why they have withheld records from the national centre.

Windspeaker.com reached out to Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller, however Miller’s staff said he would not be able to respond by deadline.

Support is available for those affected by their experience at Indian Residential Schools and in reading difficult stories related to residential school. The Indian Residential School Crisis Line offers emotional and referral services 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419. In Saskatchewan, the Regina Treaty Status Indian Services at 306-522-7494.