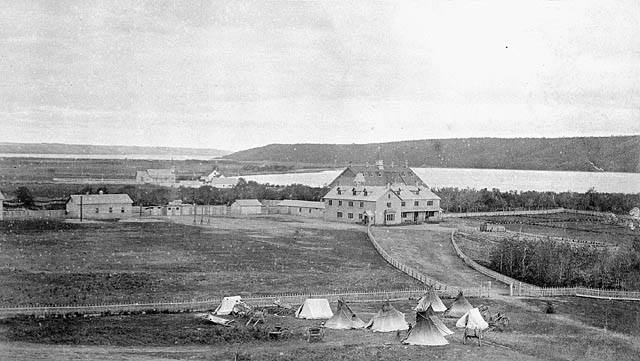

(Photo of the Lebret Industrial School)

By: Shari Narine, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Windspeaker.com

WARNING: Disturbing content

The Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples may have been shocked two weeks ago when witnesses told them about the difficulties they were having in accessing Catholic Church records for children who attended Indian residential schools, but this morning Senators did little to push representatives from the archdiocese and oblates on the issue.

The Senate Committee, chaired by Mi’kmaw Senator Brian Francis from Prince Edward Island, today heard from Archbishop Murray Chatlain of the Archdiocese of Keewatin-Le Pas, Father Velichor Abaranam Jerome, general archivist of the General House in Rome, and Father Warren Brown, representative of the OMI general administration.

The Senate Committee is holding a series of hearings as follow-up to recommendations included in their interim report, Honouring the Children Who Never Came Home: Truth, Education and Reconciliation, released last July.

The Senate Committee dismissed as a “misunderstanding” previous testimony from Raymond Frogner, head archivist at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation NCTR), when Brown said it was the first time he was made aware of claims by Frogner that when he was in Rome he was unable to copy personnel records of at least 12 oblate priests convicted of crimes against children at the schools.

Jerome noted that privacy laws were stricter in the European Union, where the Rome facility is located.

When asked by Senator Scott Tannas of Alberta if those privacy laws could present an issue, Jerome said, “Each time we do any (records) activities, we do consultation with the lawyer to see whether there are any laws preventing (disclosure). So far, we have not come across any difficulties.”

As for the sharing of sacramental records available in Canada, Chatlain said a memorandum of understanding was being developed with the NCTR that would follow guidelines for historical sacramental and death burial records.

“Sacramental registers are some of the church’s most precious records and a sacred trust. They hold vital records of personal and civil importance and so must be maintained in accordance with the privacy provisions under both federal and provincial civil law,” he said.

The Senate Committee heard in testimony in preceding months about the importance of these sacramental records in gathering, in particular, burial information. They also heard how sacramental records were held by each diocese, which made them difficult to track down.

Chatlain said to do a “national kind of thing (for the sacramental records) would be very challenging.” He urged people to continue to contact their local diocese.

Chatlain said they were open to sharing funeral records as they were already “pretty public,” appearing as funeral notices and obituaries, but baptism records, which include the names of parents, could be more difficult. However, they could work with the NCTR to redact private information.

“We are trying to focus on being collaborative and helping. Whether it is in Saskatchewan or Manitoba, we haven’t really found legislation that’s hampered that. It’s more trying to be sensitive to the privacy of families,” he said.

However, on Oct. 25, Saskatchewan Treaty Commissioner Mary Musqua-Culbertson told the Senate Committee about numerous incidents where the Prince Albert diocese gave her staff difficulties as they tried to access residential school records, including promising to release records and then reneging on those promises.

See that story here: https://windspeaker.com/news/windspeaker-news/senate-committee-shocked-difficulties-faced-gathering-residential-school

Musqua-Culbertson’s comments, along with accounts from Frogner, prompted Senator David Arnot, former chief commissioner of the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission and federal treaty commissioner, to comment Oct. 25 that the testimony was a “litany of frustration with the non-compliance truculent stonewalling purposeful barriers” that was being faced by those trying to gather records from the Catholic Church.

Arnot was not present at today’s hearing.

Alberta Senator Karen Sorenson once more raised the possibility of former residential school staff and administrators as “living archives” who should consider sharing their knowledge with Indian residential school survivors.

“(They) could have valuable information about the events that took place at these schools, including where sick or injured children may have been sent and what happened to the remains of students who died…Survivors and their family members are aging and, to put it bluntly, at the current rate, people will continue to die before they find out the truth,” she said.

Sorenson didn’t receive a commitment from Catholic Church representatives.

“Interviewing living people depends on the provincial superiors in Canada because they have the full authority over it,” said Jerome.

Francis asked Chatlain about what the church was doing to combat residential school denialism.

“I have seen firsthand how prevalent this issue is in church and how important it is for governments and churches responsible for the Indian residential schools, and other institutions, to be transparent and accountable,” said Francis.

Chatlain said that while it was challenging to address racism in the church, he has been “pretty outspoken for many years about the history.”

Support is available for those affected by their experience at Indian Residential Schools and in reading difficult stories related to residential school. The Indian Residential School Crisis Line offers emotional and referral services 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.