By: Shari Narine, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Windspeaker.com

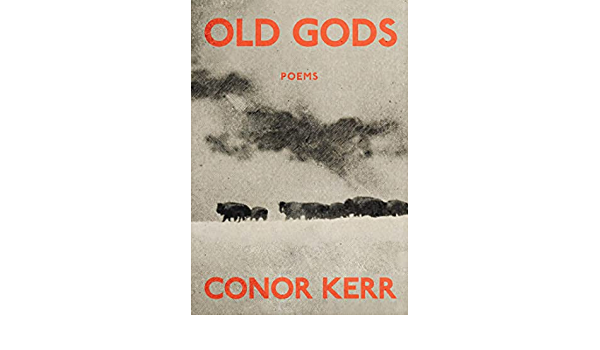

Anger and hope. They seem incongruous, but not in the writings of Métis Ukrainian author Conor Kerr as he weaves these emotions through the pages of his newest poetry collection Old Gods.

Kerr’s words vividly and powerfully capture his childhood memories and feelings around his late Métis grandfather, family recollections, his travels in Saskatchewan, and his time spent in Edmonton.

“It’s quite autobiographical,” said Kerr of Old Gods. He’s a descendant of the Lac Ste. Anne Métis and the Papaschase Cree Nation. “I almost wanted to, at one point, call it a poetic memoir.”

And while Kerr stresses that the sentiments are true to him and his family, he’s confident that many other Métis will share these same feelings and thoughts.

Take for instance the question of Métis identity, which suffuses almost every line in the book in a heartfelt longing for the deep connection to his traditional territory.

The long prose poem “Just Passing Through” expresses his heartache.

“The road glistens with sweat from every job I failed to perform at until put on a pedestal to ANNOUNCE my heritage and family stories for the validation of white institutions. Am I NDN enough for you? For you to listen to me?”

“I think one of the things that I wanted to raise within the book is that question…How does colonialism define Indigenous identity, but also how do Indigenous communities define identity?” said Kerr.

“I think the identity question is something that we need to constantly be talking about. But for myself and my family, there’s never any doubt as to who’s Métis and who’s Métis around us because you respond within those kinship ties and connections.”

Those connections for him and his family, said Kerr, and many of his Cree and Métis friends, are “within…a prairie landscape that I love and I adore and I feel welcome in and I want to be in.”

He indicates his reverence for that landscape by spelling prairie as “prayerie.”

“I wanted to almost form this kind of religious sentiment…to have more of that prayer and effect and being that the land itself is a form of prayer,” he said.

But land is only one of the old Gods. Kerr says old Gods show themselves in the rivers, in the birds and in the animals, too.

Kerr also raises identity as a question in light of the false Indigeneity claimed by scholars, including University of Saskatchewan Professor Carrie Bourassa and former judge Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond.

There are people, who are trying to “reap…so-called benefits…without any of the historical connections or contemporary connections to community,” said Kerr. They “have really displaced a lot of Indigenous people who should be having access to those positions of power.”

In the poem “Investment,” Kerr delivers another powerful line: “I’m angry on the page because I don’t know how to turn off a smile.”

In the bureaucratic institutions he’s worked in, Kerr says it’s never more than “talk a little bit about beadwork; sample some bannock.”

“(In) these spaces…and this is incredibly brutal, but to be successful as an Indigenous person, you need to be harmless. You can’t be a threatening person in any way or else it upsets the entrenched colonial system,” he said. “They don’t want any actual systemic change that will address the intergenerational traumas and colonialism.”

His survival mechanism in his younger days was to smile, Kerr told Windspeaker.com.

“I don’t need to do that as much anymore, which is pretty fortunate. I also just got to the age where I just don’t care as much so I’ll tell people straight up how it is,” he said.

And he also expresses his “critical feelings” within his writing.

That anger and those indulging smiles have given way to hope, says Kerr.

“A lot of this book talks about a kind of, almost, displacement from our own homes, our own territories and the spaces, and calling that back, trying to reclaim that,” he said. “I think a portion of that comes back to those knowledge systems that haven’t gone away.

“Colonialism is a micro-blurb in the long, long, long histories of these spaces, and so these old Gods are around us and within us still. And they’ve never left. They’re still here. And they’re coming back strong.”

Kerr’s final prose poem in Old Gods, “What Do You Believe In?” ends with the lines, “Believe in the words and the way that pride is written all over the faces of those who learn what it means to own ourselves. To never bow under hell on earth. To never step back but always move forward knowing that within this landscape we are reborn, awoken, brought back by the artists and the writers, the poets and the dancers, the musicians and the lovers, the beaders and the hunters./Because I do. /I believe in everything.”

“People have been pushing, pushing, pushing for the past 150-plus years of colonialism and starting to really set that tone now,” said Kerr. “And I feel like we’re really seeing this with the content explosion from Indigenous peoples by Indigenous peoples for Indigenous peoples that we haven’t necessarily seen in the past before…All of it is very inspiring.”

For Métis readers, Kerr hopes that within his work they find a space for “the creation of strengthening identity, strengthening cultural background and strengthening the knowledge that you belong to a community, to a kinship network, to the land.”

For non-Indigenous readers, he wants them to “really think critically” about the lands they live on.

In “Wishing on a Walleye,” he writes, “I wish the Oilers won the cup and then they turned the arena into the Papaschase Reserve./ I wish they gave all that 50/50 money back to the people whose land they’re playing hockey on.”

The Papaschase people lost their status despite signing an adhesion to Treaty 6 in 1877. According to band history, members were removed from their lands and forced to join other nearby First Nations or enticed to take scrip (financial vouchers in exchange for land and Treaty rights) during a time of starvation.

Kerr wants non-Indigenous readers to go beyond the trite “we love the culture, we love going to the powwow at Enoch or going to these round dances” and engage in meaningful talk and actions.

“When people start talking about, ‘Oh, we’ve come so (far).’ No. No, we really haven’t, from the settler’s standpoint. Indigenous communities, we have come a long ways, and settlers, not so much at this point. We need to get above these ideas of stereotypical reconciliation or decolonization, Indigenization, all of those buzzwords, and get something real to happen,” said Kerr.

Kerr wrote the poems for Old Gods during a two-year period. “Just Passing Through” was written for a contest for the Malahat Review during the coronavirus pandemic at a time when he was feeling sad and being reflective.

While Kerr won the Review’s long poem prize, he says the contest was more beneficial because “it gave me a good spark to write something. I don’t think I would have necessarily created a poem to that length if it was just me sitting around trying to compose stuff. It probably still would have been just these one-line poems here and there.”

Not all his poems were included in Old Gods and will be used for a future collection, he says.

An Explosion of Feathers is Kerr’s first published poetry collection. His novel Avenue of Champions was longlisted for the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize.

Old Gods is published by Nightwood Editions and is available in bookstores and online https://harbourpublishing.com/products/9780889714465